From the deserts of Arabia to the rainy streets of London, and from the towering glass needles of Manhattan to the most famous tower of them all in Paris, we’ve gathered together some interesting stories about a few of our favorite destinations. A bit of history, a bit of myth, and a few surprises – here’s a trip round the world with Musement.

From battles to Bond

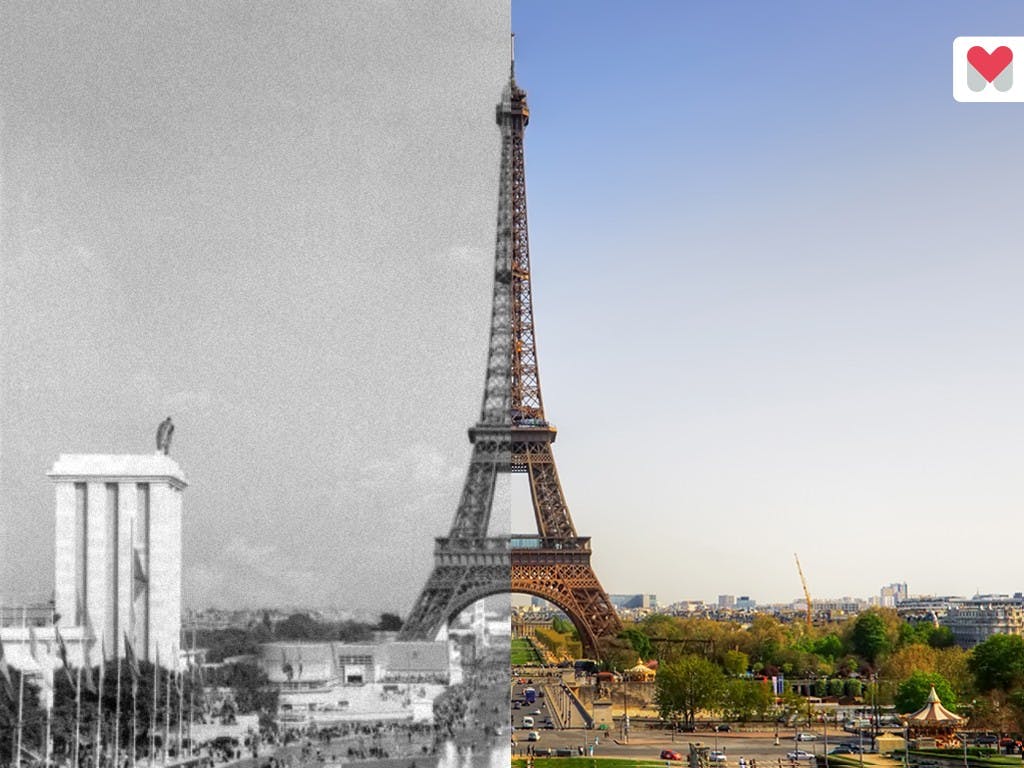

The Eiffel Tower, Paris

The Iron Lady

No Paris landmark is as emblematic as the Eiffel Tower, a 300-meter tall wrought iron structure jutting out from Champ de Mars to overlook the serpentine river Seine, Haussmann’s zinc rooftops and the histories and secrets living within the City of Light’s storied streets.

Architect Gustave Eiffel built the tower in honor of the 1889 World’s Fair commemorating the centennial of the French revolution, originally intended to just be a 20-year installment. Russian, French and Flemish restaurants sat on the first floor while Le Figaro newspaper set up shop on the second. Visitors to the top floor could send postcards to loved ones on the spot in the post office.

At the time of its completion, the Eiffel Tower was the world’s highest manmade structure. In its 127 years and counting lifespan, the tower assisted with the Battle of the Marne victory, having interfered with German radio conversations; survived Hitler’s order for its destruction; and has stood tall as pilots have flown through its arches.

The landmark has made many a cameo in films from contemporary flicks like The Devil Wears Prada and Midnight in Paris, to Audrey Hepburn classics including Paris when it Sizzles and Funny Face. James Bond’s A View to Kill depicted a scene in the tower’s one-star Michelin rated Jules Verne restaurant, while Christopher Reeve in Superman saved the Eiffel Tower (and Lois Lane in the process) from a destructive attack.

Nowadays, the top floor boasts much more than a view. Enjoy a toast while admiring the best vista in town at the Champagne Bar and step inside Gustave Eiffel’s private penthouse apartment, now open to visitors. The Jules Verne restaurant is still going strong on the second floor. At night, watch the tower sparkle every hour on the hour for five minutes.

Napoleon stole my horses!

The Brandenburg Gate, Berlin

Brandenburger Tor

The Brandenburg Gate was initially part of the Berlin Customs Wall – limiting the import and export of goods in order to better levy taxes. The structure was also meant to stand as a symbol of peace, but since its completion in 1791 it has taken quite a beating.

In 1806, Napoleon pilfered the Quadriga on top – a statue of a chariot pulled by four horses with an olive wreath held aloft. Prussia took the statue back in 1814 and changed the wreath to oak leaves with an iron cross and eagle – a symbol of victory for the kingdom.

Flash forward to 1945. The gate had survived the destruction of World War II, but it was heavily damaged. Restoration began, patching up bullet holes and missing pieces, but everything came to a halt due to icy relations between East and West Berlin. Even after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, restorations were not fully completed until 2002 when the Gate was officially re-opened to the world.

Today, the Brandenburg Gate stands in the middle of a large pedestrian square, contributing more to tourism than levying taxes. It looks well maintained and fairly new, hiding over 200 years of damage from history. However, despite the Brandenburg Gate’s tumultuous past, it continues to be a strong symbol of peace and unity – for Germany as well as all of Europe.

‘Pretentious’, ‘absurd’ – a legend

Tower Bridge, London

Tower London

This is London’s most iconic bridge. Featured in a slew of movies that go from The Elephant Man (1980) to Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), it’s almost impossible to have a movie set in London without a 30-second cameo of its blue exterior. For most of us it’s no longer just a bridge, it’s synonymous with the city itself.

But this wasn’t always the case. When the bridge was finally unveiled (1894), while it was the largest and most sophisticated bascule bridge ever built, it suffered criticism both for being ‘pretentious’ (by architectural expert HH Statham) and ‘absurd’ (by Anglo-Welsh artist Frank Brangwyn). Many people disliked its Victorian Gothic design. Additionally, while it’s hard to imagine now, its high level walkways also became known as a haunt for prostitutes and pickpockets; the walkways had to be closed in 1910.

At the time, the bridge served a very necessary function. Crowding in East London was becoming a problem and there was only one bridge across the Thames (the nondescript London Bridge that Tower Bridge is often confused with). Today, the bridge is a massive tourist attraction. People come from all over to witness the raising of its roadway or to experience the panoramic walkway views.

It’s also changed its ‘look’. It got its first red, white and blue paint job in the ’70s for Queen Elizabeth II‘s Silver Jubilee. In 2014 glass floors were installed in the walkway, giving passersby compelling vertiginous views. Now there are plans for a GBP 20 million light installation in all of London’s major bridges, which will see the elegant bridge transformed into a modern piece of art.

Nearly finished – honestly!

Sagrada Familia, Barcelona

Sagrada Familia

Antoni Gaudi’s Expiatory Temple of the Holy Family is still famously unfinished after 134 years. The ancient Pyramids of Giza in Egypt took less time to complete. What’s the problem?

The Sagrada Familia has had a colorful history. Its initial architect in 1882 was Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozan, but he argued with the promoters and resigned very early. Gaudi took over and decided not to continue with the original Neo-Gothic design, suggesting something much more ambitious and symbolic. It wasn’t until 1923 that he produced a final design for the roofs and nave.

The first bell tower (on the Nativity façade) wasn’t finished until 1925, but Gaudi wouldn’t see any more towers completed. In 1926, aged 74, he was hit by a tram and died three days later – his body initially unidentified because he looked like a vagrant. Fortunately, he’d left architectural plans in his workshop. Unfortunately, anarchists stormed the building in 1936 and destroyed the plans. Reconstructed diagrams continue to be controversial, with some saying that the current vision is not at all what Gaudi intended.

The architect himself was philosophical about delays, claiming that his client (God) was in no hurry. Construction continues today and the latest plan is to finish the cathedral on the 100th anniversary of Gaudi’s death in 2026. In the meantime, three million people visit annually, making it Spain’s most popular attraction.

Gaudi took one great secret with him. There’s a stone-carved square on the Passion facade (next to the kissing statue) featuring a 4×4 grid of 14 different numbers. What do they mean? Some say the numbers add up to 33 when read vertically, horizontally or diagonally – the age when Christ died . . . or is it the highest rank in Freemasonry?

No actors, no gravediggers

The Colosseum, Rome

Colosseum

As you stand looking at the ruined stone and exposed foundations of Rome’s Colosseum, take a moment to consider that more than one million animals and around 500,000 humans have been brutally slaughtered in this place – for entertainment.

The Flavian Amphitheatre – its official name – was a wonder when completed 80AD. With capacity of 50,000 spectators, it was created partly to fuel the popular demand for games, partly as a statement of power for the Flavian dynasty and partly as a showcase of Roman architectural skills. Mostly, it was about death and killing.

Here, gladiators fought each other and were also used as executioners of criminals or runaway slaves. Christians were allegedly martyred and wild animals from across the world were ‘hunted’ in free shows that sometimes ran for up to a hundred days. That’s a lot of animals. Nor was it only the commoners who attended – nobles and senators had their own special seating (but actors and gravediggers weren’t allowed at all).

The eventual decline of Rome, and perhaps a change in the public appetite for mass murder, saw the amphitheater gradually fall out of use. Rain and wind assailed it. Lightning struck it. In 847, the whole southern side collapsed in a massive earthquake. Local people also began to use it as a convenient source of building materials and its marble facades were actually used to construct part of St Peter’s at the Vatican.

Today, the Colosseum is Rome’s most popular attraction and millions come to learn about its history. Where once the crowds observed hideous carnage, now Elton John or Paul McCartney perform their hits.

Made with wooden hammers?

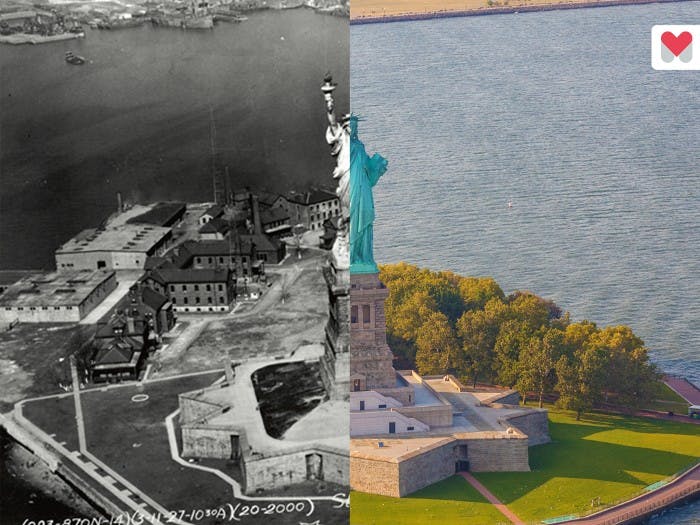

The Statue of Liberty, New York

Statue of Liberty

French sculptor Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi was a good son. He loved his mother Charlotte so much that he used her face as inspiration for the Statue of Liberty. Sadly, we’ll never know how Mrs Bartholdi felt about becoming so famous, so massive and so . . . green.

Lady Liberty has her origins in an idea of French politician-professor Edouard de Laboulaye, who wanted to give a gift to America in recognition of its independence and abolition of slavery. His statue would be called Liberty Enlightening the World and would be designed by Bartholdi with a little help from another Frenchman with a familiar name: Gustave Eiffel (architect and fan of towers).

The statue was not entirely built in America. Its 300 pieces were made in Paris from copper sheets only 0.094 inches (2.4 mm) thickness that were then hammered to shape using a variety of wooden hammers. These were then shipped to New York and assembled on Eiffel’s iron spine. When completed, it was the world’s highest iron structure and had cost a total of USD 10 million in today’s money. For 16 years (1886-1902), she earned her living as a lighthouse, warning shipping up to 24 miles away.

The statue holds a golden torch of enlightenment (replaced and re-gilded in the 1980s) and a tablet inscribed with date of the American Declaration of Independence: July 4, 1776. She also stands on broken chains, representing emancipation. Perhaps more famously, her head was discovered on a beach by Charlton Heston in Planet of the Apes (1968) and exploded/washed away in Independence Day (1996) and The Day after Tomorrow (2004).

It’s all about the bedrock

Manhattan skyline, New York

Manhattan skyline

In Manhattan, the only way is up. With land so limited and so valuable, developers have been heading for the clouds since the nineteenth century, when the skyscraper was born.

Chicago was initially New York’s main competitor for the country’s tallest buildings at a time when traditional stone or brick structures were reaching their safe heights. The iron skeletons of skyscrapers allowed buildings to rise ever higher and NYC eventually triumphed with a series of epic towers including the Chrysler Building (1930) and Empire State (1931). The original World Trade Center in 1972 gave Manhattan the crown.

One World Trade is now officially the tallest in New York – or is it? There’s another, strange matchstick-like, tower that seems higher than everything else in this glass forest. In fact, 432 Park Avenue has a higher rooftop – only the lack of an antenna makes it officially shorter. Whichever rules, there are plenty of giants: One57, 40 Wall Street, Beekman Tower, Trump World Tower and 30 Rockefeller Centre to name a few.

A curious fact: NYC’s tallest buildings are either Downtown or Midtown. Why is that? It’s a question of bedrock, which is near to the surface in those two areas (see big bits of it in Central Park) and provides a powerful foundation for tall buildings. South of 30th Street, the rock is under sediment – hence smaller buildings.

But where to view the skyline? The Empire State building’s observatory is famous, but you’re better going to the Rockefeller Center if you want to actually see the Empire State. The promenade over Brooklyn Bridge is another good lookout, as is the café on top of the Met gallery. For a really majestic view, however, take the Staten Island ferry and glance back at Manhattan as you pass Lady Liberty.

I can’t move my hands!

Big Ben, London

Big Ben

As most British schoolchildren know, Big Ben is not a building. The well-known clock at the north end of the Houses of Parliament sits the Elizabeth Tower, completed in 1859. ‘Big Ben’ is the large bell inside it – a bell with a difficult history.

The original was made in 1856 and arrived at Parliament in a carriage pulled by 16 white horses. Unfortunately, the bell cracked when struck – perhaps because the hammer used was too heavy. A second, lighter, bell was made in 1858 but was too large to fit up the tower vertically and had to be hand-winched sideways for thirty hours. This new bell also broke when struck. A smaller hammer was suggested and a small hole was cut in the bell to stop the crack growing. It’s the same bell that rings every hour today. Why ‘Ben’? It’s probably named after Sir Benjamin Hall.

The clock mechanism was built by John Dent and the giant clock face was designed by Benjamin Vulliamy, the Queen’s Clockmaker. Alas, the problems wouldn’t end. At first, the clock tower was too small to accommodate the clock. Then the cast-iron minute hands were too heavy to move and had to be replaced by copper. But when finally completed, the four clock faces were magnificent: each one seven meters in diameter and made of 312 separate pieces of opaque glass.

In 2016, the government announced a three-year repair and refurbishment program for Big Ben (beginning in 2017). For the first time in many years – and after the bombings of two world wars – the bell will go silent for a few months. But the news is good: Big Ben will emerge better, cleaner and stronger, with an elevator replacing the 334 steps to the top. Ding dong!

Archbishop in a basket

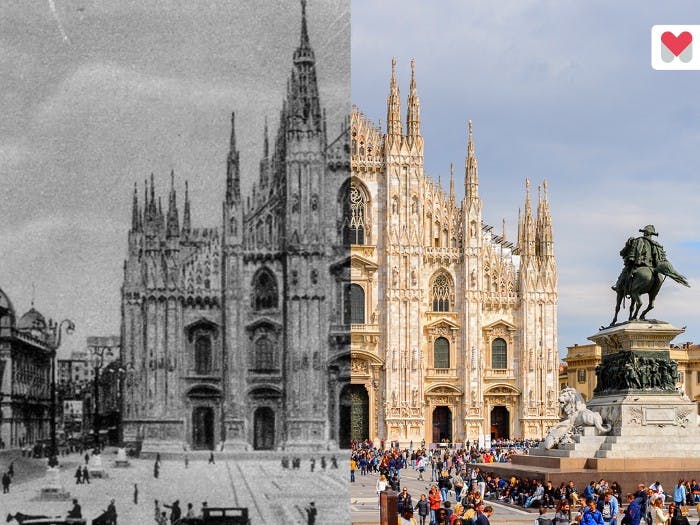

The Duomo, Milan

Duomo, Milan

What do Milan’s Duomo and Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona have in common? They’re both technically unfinished. The Spanish cathedral has taken 134 years, but Milan’s has been going for more than 600!

Begun in 1386, the Cathedral of St Mary Nativity became a brick building with a façade of pink-white Candoglian marble from Lake Maggiore. Canals were dug to transport the stone and still exist today in the city’s Navigli district. Meanwhile, thousands of masons and sculptors arrived in Milan over the centuries to work on the 3,400 statues, 52 pillars and 135 spires/pinnacles. It’s now Italy’s second largest church, losing only to the colossal St Peter’s in Rome.

Of course, you’d never guess the Duomo isn’t finished. Much of the ongoing work is restoration, cleaning and repair – though some statues do remain uncarved. The view from the roof, up among the gargoyles and spires, is probably the best in the whole city, while its massive western face is a stunning presence in the Piazza del Duomo. Thank Napoleon Bonaparte for the façade. He ordered to be completed in 1805.

There are religious treasures here also. The red light high above the altar marks the place where an actual crucifixion nail is said to rest, and from where it’s retrieved each September by an archbishop hoisted aloft in a sixteenth-century basket. The sarcophagus of St Charles Borromeo, meanwhile, is a lavish glass construction with the body of the saint visibly reclining within. To the left of the altar is the famous statue of Saint Bartholomew by Marco d’Agrate (1562) – a grisly portrayal of the martyr who had his skin removed. Here, he wears it casually over his shoulder like a cloak.

Made with ice water

Burj Khalifa, Dubai

Burj Khalifa

Yes, it’s the world’s tallest building at 828 meters (2,716.5 feet) and more than 160 stories. It also has the highest outdoor observation deck and the highest nightclub. Amazingly, it took only six years to construct.

And what a construction! There are skyscrapers in New York, but New York doesn’t typically have daytime temperatures of 50 °C (122 °F) and non-stop blazing sunshine. Such things make the design and building process difficult. For example, the concrete used in Burj Khalifa was mixed especially to withstand the immense weight, and was mixed only at night when temperatures and humidity were lower. In the summer months, ice water was used because concrete cracks if it dries too quickly. That’s not good.

The startling design of the building stems from a combination of factors. The Y-shaped profile was chosen because it provides good layouts and frontage for residential and hotel space (with the added benefit of allowing buttresses for extra strength). As for the tapering shape, this acknowledges patterns in classic Islamic architecture such as the spiral minaret. The shimmering glass and aluminum cladding system is designed to reflect the desert heat.

Rising from the desert as a silver pinnacle that dwarfs everything around it, Burj Khalifa is a wonder of modern architecture and a symbol of Dubai. Hollywood evidently also feels the glamor – you may have seen Tom Cruise dangling from the exterior in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011).