Here’s a look at some of the intriguing, lesser known aspects of Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece

Anyone who grew up in Milan during the 1990s is likely to have fond memories of Sunday afternoons at the Museum of Science and Technology, school trips to the Pinacoteca di Brera, Disney films at the Cinema Nuovo Arti, and the seemingly endless line at Santa Maria delle Grazie to view Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Though you still have to book in advance, it’s much easier to admire Leonardo’s masterpiece today than back in the days of yore, when one had to call the ticket office and sign up for a spot on a long waiting list.

Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, commissioned The Last Supper to Leonardo as a way of embellishing the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in honor of the Sforza family. While working on the decoration of the refectory, Leonardo settled in the Casa degli Atellani across the street and remained there for the three years he spent working on the painting.

Everyone knows the artistic and symbolic importance of The Last Supper, and many are convinced that they know the painting’s deepest, darkest secrets thanks to Dan Brown. However, there are some aspects of Leonardo’s masterpiece to which not everyone is privy. So, here are six things that (perhaps) you didn’t know about The Last Supper.

1. The Last Supper is deliberately anachronistic

Leonardo chose to set the world’s most iconic meal in fifteenth-century Milan. The table at which Jesus and the apostles sit, as well as the utensils and tablecloths, have been painted to match those that were in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie at that time. The idea was for the painting’s table to blend right into the refectory dining tables as though Christ and the apostles were dining together with the Dominican monks who inhabited the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

2. Johann Wolfgang Goethe fell in love with the painting

After traveling in Italy for two years, the author of The Sorrows of the Young Werther visited the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1788 on his way home to Germany. Johann Wolfgang Goethe did not appreciate the Lombard capital (he even called the Duomo “an absurdity”!), but he literally stood in ecstasy in front of The Last Supper. He loved it so much in fact, that he embarked on an in-depth study of the painting and wrote an essay to celebrate Leonardo’s masterpiece. Published in February 1817, Goethe’s work aimed to make The Last Supper accessible to the widest possible audience.

The refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, home to Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Photo credit: Dimitris Graffin via Visualhunt.com / CC BY

3. The Last Supper captures the Italian spirit

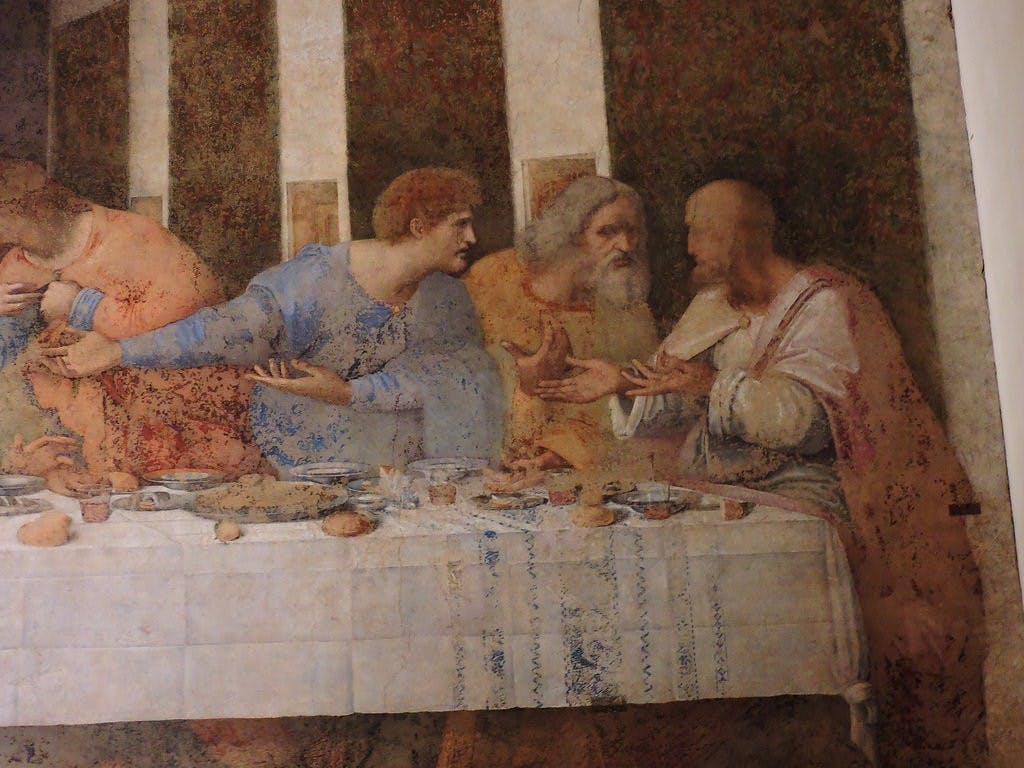

The Last Supper portrays a moment of tremendous upheaval: The exact second after Jesus announced that one of the apostles will betray him. This news naturally upset the peaceful mood and conviviality of the meal, and the apostle’s dismay is reflected in their agitated gestures. Goethe wrote that only an Italian could best illustrate this representation as Italians are full of spirit, using every body part to convey expressions of feeling, passion and thought. Peter, who isn’t seated beside Jesus, stretches forward and grabs John’s right shoulder with his left hand, as if urging him to elaborate on who will be the traitor. James bends backward in dismay with his arms widened while Philip beats his chest to prove his innocence. Thaddaeus has a hand in the mid-air ready to strike. Judas, the traitor of the bunch, leans away from the group, his face masked by shadows while his right hand tightly clutches a bag of silver, the price of his betrayal.

4. A series of unfortunate restorations: A fraud, an incapacitated person and Napoleon’s inept general

Although often referred to as a fresco, The Last Supper technically is not as Leonardo invented a particular mix of oil and tempera plaster to paint his 15-by-29 foot masterpiece, which ultimately made the color start to peel shortly after Leonardo finished it. This coupled with the humidity in the refectory caused the painting to deteriorate. The Last Supper underwent its first of many touch-ups soon after completion, but it is thanks to the twenty-year restoration completed in 1999 that we can now admire the Last Supper as it is today. Restorers who intervened along the way only worsened the situation, one, in particular, being artist Michelangelo Bellotti. In 1726, he claimed to have a miraculous product that would restore the painting back to its former splendor, but the result was far from satisfactory. Four years later, Pietro Mazza, a lesser known and even lesser talented painter, took on a restoration that only further besmirched Leonardo’s masterpiece. As if that wasn’t enough, when the French troops crossed the gates of Milan in 1796, Napoleon immediately went to visit The Last Supper. He ordered the hall be closed to preserve the work, but a general who missed the memo had the door to the refectory broken down and converted the space into a stable. In April 2017, an environmental restoration project was announced for the sanitation of the painting’s microclimate, which is made possible thanks to a fund partially financed by Eataly, the worldwide, Italian food hall giant.

Close-up of the gesture of Thaddaeus. Photo credit: Dimitris Graffin via Visual Hunt / CC BY

5. The Last Supper is a representation of Cosmos: astrology and occultism

It’s no secret that Leonardo da Vinci was not only a painter but also a scientist, inventor, and mathematician who studied botany and philosophy in addition to astrology and occultism. Thanks to the Codex Atlanticus, we know that these last two fields occupied an important place in his studies. In fact, astrology had a strong presence in Renaissance culture, and even mathematics was imbued with esotericism and magic. Therefore, it is not surprising that The Last Supper can also be interpreted as a representation of the solar system and the zodiac, with each apostle showcasing the characteristics of each zodiac sign. For example, Thomas corresponds with the planet Mercury and the sign of the Virgin Mary, while Peter is in the position of Jupiter and the Sagittarius. The leader of the apostles and founder of the Catholic church is described in the Gospels as a man of great nobility, but unstable and uncertain just like the fire sign he represents; he looks like he’s about to jump to his feet with same dynamism as the arrow from the arch of the Sagittarius. Judas instead represents Scorpio, in the position of Mars, an unfaithful sign that represents disintegration and death; his fingers are contracted like the scorpion’s pincers ready to attack. Jesus is the Sun illuminating the scene and the universe with his divine light.

6. The Last Supper in Pop Art

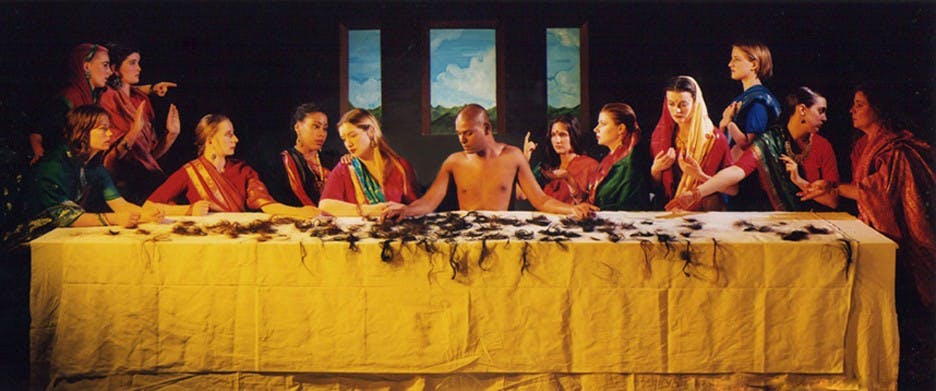

Italo Calvino said that a classic “has never finished saying what it has to say”, and if this is true for novels, then it most certainly applies to art. Countless replicas of The Last Supper exist, made from a number of techniques by different artists over the centuries. Giacomo Raffaelli made a mosaic replica for Napoleon, and in the Chapel of Santa Kinga you can admire the Last Supper carved in the rock of a Wieliczka salt mine. Many important contemporary artists have also paid homage to the masterpiece: Andy Warhol created 60 Last Suppers during the last years of his life, while in 1998 George Chakravarthi — who is known for highlighting the beauty of both cultural and gender diversity in his works — reworked the image to portray a disrobed Christ surrounded by 12 women dressed in saris for his Resurrection work. David Lachapelle, a photographer whose provocative works are characterized by irreverent subjects, desecrating combinations, and blinding colors, re-interpreted The Last Supper for his Jesus is My Homeboy series. In the photo, Christ sports a neck tattoo and is attired in the original Leonardian colors, while the casually dressed apostles eat burgers and drink beers at s table covered with a plastic cloth.

George Chakravarthi’s “Resurrection”, photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Resurrection_by_George_Chakravarthi.jpg#/media/File:Resurrection_by_George_Chakravarthi.jpg

Sources:

J. W. Goethe, Il Cenacolo di Leonardo, Abscondita, Milano 2004 con postfazione di M. Carminati.

P. C. Marani, Il Genio e le Passioni. Leonardo e il Cenacolo, Skira, Milano 2001.

F. Berdini, Magia e astrologia nel Cenacolo di Leonardo, Bulzoni, Roma 1982 con saggio critico di F. Mei.